America's growing involvement in Vietnam during the 1950s was part of a long process of American expansion dating back to the country's founding. During the nineteenth century, American policymakers and intellectuals invoked the idea of "Manifest Destiny" to frame American expansion further westward into North America. "Manifest Destiny," a rhetorical ideal based on a conviction in the exceptional nature and virtue of the American democratic project, often clashed with the realities of brutal wars of conquest this provoked, as well as the institution of slavery at the heart of many American expansionist projects. As the United States reached its current continental limits at the end of the nineteenth century, American expansion continued. As a result of the 1898 Spanish-American War, the United States assumed de jure or de facto control of many former Spanish colonies, including Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. "Informal" forms of American empire, primarily through political and economic influence, grew steadily in Latin America during the first half of the twentieth century, as did American involvement in East Asia. The First World War brought America's global presence to new heights, primarily through participation in the European conflict, extensive aid to Allied powers, and president Woodrow Wilson's extensive role in crafting a postwar peace. Despite strong isolationist currents in American society and politics during the Great Depression of the 1930s, American colonial rule and "informal" colonial influence, as well as a growing global awareness among increasingly literate Americans, prefigured the nation's new global role during World War Two and the Cold War. American military participation and economic aid were not only decisive to the outcome of the Second World War, they brought about huge changes in an American economy driven by powerful links between the military, private industry, and the federal government. With the decline of European empires, American efforts to preserve and extend its own interests and that of its allies would bring the nation's global involvement to new heights during the Cold War.

The "Cold War" is often used to refer to the principal global dynamics of the post-World War Two era. The United States and the Soviet Union emerged from the Second World War as the two main global powers, each organized around competing ideological and political systems largely hostile to one another. The destruction of Europe during the war, and the collapse of European colonial empires this occasioned, led to postwar competition between the United States and the Soviet Union to protect and extend their respective global spheres of influence. A combination of aid projects, diplomatic initiatives, ideological campaigns and military interventions in Europe left the continent effectively divided by the early 1960s. At the same time, both the United States and the Soviet Union sought influence in the so-called "Third World," a Cold War-era term for the non-aligned world, made up mostly of former colonies transitioning to independence. This process also took various forms: economic aid, ideological campaigns, diplomatic and economic pressure, and military interventions, both through direct American and Soviet participation as well as military and diplomatic support for client states. During the 1960s, tensions between the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China led to a political split in world communism and normalization of relations between China and the United States. The Cold War is often seen as having ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the turn in communist China towards a capitalist-style economic system in the late 1980s. However, many of its political, economic and military dynamics continue to shape global affairs in the present day.

The transition from colonial rule to independence, primarily in Asia and in Africa, was one of the most important global dynamics after World War Two. The process of decolonization varied immensely from place to place. In some places, independence resulted from largely peaceful negotiations between former colonial rulers and subjects. In others, independence only came about through conflict. While certain wars of decolonization were relatively brief, others lasted many years and brought terrible devastation to newly independent nations. The Cold War and decolonization were fundamentally linked. American and Soviet competition for political and economic influence gave many wars for independence a global dimension by transforming local conflicts into international diplomatic issues or, in certain cases, by escalating military conflicts through military aid or direct intervention. Decolonization was thus often terribly divisive, as the Cold War intensified internal conflicts about the political futures of new nations. Decolonization was also a profoundly cultural process, involving the restructuring of national institutions as well as reimagining of personal, group and national identities. Continued political, economic and cultural ties between colonies and former ruling nations complicated the process of decolonization. Many local elites with close ties to colonial rulers kept power after independence, and the growing power of multi-national corporations and global financial institutions in the second half of the twentieth century have led to many "independent" nations remaining in positions of dependence for decades after the end of colonial rule, a phenomenon often described as "neo-colonialism." Decolonization is thus a complex, arguably continuing transition rather than something achieved by the fact of political independence.

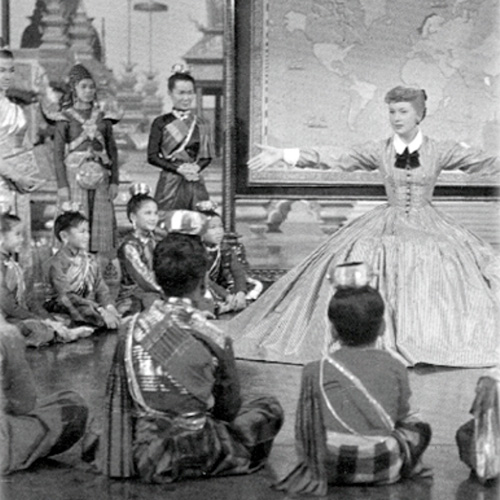

As the United States became increasingly engaged with the decolonizing world after World War Two, American policymakers and citizens alike approached and understood this process through a powerful set of paternalistic discourses about and images of the world outside of the west. These ideas often rested on imagined binary oppositions between civilized and not, white and not, Christian and not, that served both to affirm a particular definition of America and to justify its growing domination over those perceived to exist outside of it. This phenomenon had roots deep in American history, most notably in the relations of domination between European settlers on one hand, and American Indians and African-American slaves on the other. Nativist reactions to the abolition of slavery and to nineteenth century immigration were also critical, as Irish, Italian, Jewish and Chinese immigrants, and former slaves, experienced broad political, economic and social discrimination both born out of and justified by idealized conceptions of difference. As America's presence in the world spread in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, growing literacy rates and the spread of the printed word exposed more Americans to similar conceptions of Asian and African societies. By the 1950s, many Americans believed that the extension of American influence through economic, diplomatic and technical means was a necessary and salutary stage in the civilizational development of the non-western world. The politics of the 1960s laid siege to this view of the world, as global wars of decolonization and civil rights struggles at home upended longstanding assumptions about cultural and racial hierarchies that had long been at the center of American life.