Formed in 1855, the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan was the first institution of its kind in the nation. Seven years later, it was the model for the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862, whose broad federal support for agricultural schools revolutionized American higher education. The school first admitted women in 1870. By the mid-1920s, its curriculum had expanded to include subjects such as engineering, home economics, veterinary medicine and the liberal arts, and its student body was growing steadily. Reflecting this expansion, the school changed its name in 1925 to Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science. In 1940, Michigan State College had a student body of roughly eight thousand. However, the Second World War and its aftermath would bring enormous changes to Michigan State College. The person most responsible for these changes was John Hannah, who became president of the school in 1941. Hannah aggressively sought federal funding, notably the 1945 G.I. Bill, to fund the rapid expansion of the school's physical plant, academic departments, and faculty and student bodies. He also founded a branch campus outside of Detroit and oversaw the school's admission into the Big Ten athletic conference. In 1955, the school changed its name once again to Michigan State University. John Hannah remained president of MSU until 1969. In the year of his retirement, the university's enrollment was ten times what it was in 1935. The university had fifteen divisions with 104 departments, compared to six divisions with forty-four departments in 1935. The student body was academically stronger and more diverse, drawing from the entire country and many foreign countries, and the university's faculty and programs were truly global in reach. However, many students and faculty came to resent Hannah's philosophy and personal style during the tumultuous 1960s, criticizing him of overexpansion and a top-down leadership style that limited the freedom of students and faculty. Hannah resigned in 1969 to become head of the United States Agency for International Development.

During the 1950s, president John Hannah actively sought to expand his growing institution's presence overseas. On campus, Hannah formed the Institute for Foreign Studies and the Office of International Programs and supported the expansion of the university's foreign studies curriculum, including foreign languages. Hannah believed not only that MSU students should be well informed about the world, he believed that the expertise of MSU faculty had an important role to play in the expansion of American political, economic and cultural influence throughout the world. During the 1950s and 1960s, Hannah drew heavily on federal programs to fund a range of university projects overseas. The first major project was the development of the University of the Ryukus in Japan in 1951; over the next few years, MSU took up similar projects in Brazil, Columbia, Nigeria and Turkey. MSU's expertise in international agriculture also led to the university's involvement in development projects throughout Latin America and Africa during the 1950s and 1960s. Reflecting a broader cultural shift in American understandings of their country's role in the world, and thanks in large part to the university's controversial involvement with the South Vietnamese government, criticisms of MSU's international programs began to grow in the 1960s. Critics accused MSU faculty of overly close ties to American policymakers that threatened their autonomy and critical agency, and alleged that MSU faculty were unprepared for or insensitive to the cultural differences inherent in foreign research and aid work. Despite such criticisms, MSU international programs continued to grow and remain the foundation for the university's current global engagement.

During the 1950s, Michigan State University developed a unique relationship with the Republic of Vietnam, better known as South Vietnam, in the early years of the new nation's existence. In the mid-1950s, South Vietnam was attempting to transition away from the political and economic institutions that French colonialism had built and left behind. The new president of South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, saw American-style administrative and technical modernization projects as the key to political stability and economic prosperity. Because of his personal ties to Wesley Fishel, assistant professor of political science at Michigan State College, Ngô Đình Diệm requested MSC-led technical assistance as a central part of an aid package offered by the United States government, eager to support this new non-Communist country in the global Cold War arena. John Hannah, president of the college, was an advocate of expanding his institution's presence in the world as well as a staunch anti-communist, and he strongly supported these programs. What became known as the Michigan State University Group (MSUG) in South Vietnam was led by MSU faculty and focused on a range of activities. The South Vietnamese government faced a crisis of refugees streaming down from North Vietnam, and MSUG faculty advised South Vietnamese officials on questions of resettlement and economic integration. MSUG programs in public administration oversaw the foundation and organization of the National Institute of Administration, where new civil servants and bureaucrats studied; public administration programs also brought South Vietnamese to East Lansing to take courses and pursue internships. Finally, MSUG criminal justice faculty were heavily involved in the reorganization and modernization of South Vietnam's police and security forces by training personnel in techniques of criminal investigation, communications, public order, record keeping, and equipment use. By the early 1960s, the deteriorating political and economic situation had led to internal dissent among MSUG officials, as well as growing tensions between MSUG leadership and Ngô Đình Diệm. In 1962, the university's contract in South Vietnam was not renewed, and the programs came to an end.

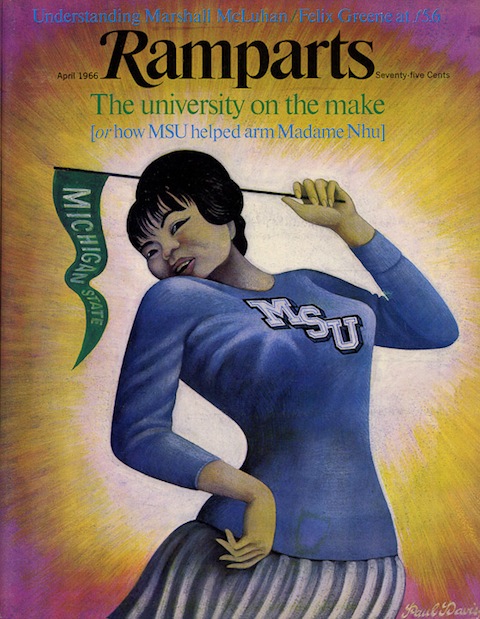

Less than a year after their creation, a number of "outside consultants" appeared on the employee rolls of MSUG police training programs. Several of these consultants were current employees of the American Central Intelligence Agency, listed as MSUG employees at the request of the CIA for purposes of cover. Although their activities were separate from those of the MSUG and remain classified, the existence of these consultants and their CIA connections were well known to MSUG officials at the time and openly mentioned in several of the group's publications. In 1966, four years after the end of the university's work in South Vietnam, an article heavily critical of the MSUG appeared in Ramparts magazine, a left-leaning Catholic publication. Although the three principal editors of Ramparts wrote the article, they received significant help from Stanley Sheinbaum, a former MSU economics professor and MSUG employee. The article, written in a sensationalized, "tell-all" style, alleged that MSUG police programs had served as a shield for covert counterinsurgency and counterespionage work, and that the university had purchased weapons for South Vietnamese police and security forces. Many of the article's revelations were either already public and some were distorted, but it had an enormous effect nationally and on MSU's campus. John Hannah gave a press conference denying the article's accusations, eliding some of its truths in the process, Wesley Fishel became a target of student protests, and former head of MSUG police programs Ralph Smuckler eventually testified before the state legislature. The Ramparts controversy was a major event in public debates over the role of universities in foreign aid programs and their involvement with American nation-building, and it has remained a central part of the memory and legacies of the MSUG.