The Republic of Vietnam, better known as South Vietnam, emerged out of the political and military conflicts surrounding Vietnam's transition from French colonial rule to independence. In August 1945, the communist-led Việt Minh ("League for the Independence of Vietnam") seized political power in Hanoi and proclaimed the independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam. French diplomatic and military efforts to regain control of their former colony erupted into the First Indochina War in December 1946. During the course of the war, Vietnamese communist leaders took power of the revolutionary state from their non-communist nationalist opponents. As the Cold War intensified and the 1949 Chinese Revolution raised the specter of a communist victory in Asia, the French, their American backers and some non-communist Vietnamese nationalists formed a new Vietnamese state in 1949, the State of Vietnam. While Western policymakers hoped that the State of Vietnam would become a friendly regime in an increasingly divided world, Vietnamese nationalists saw it as an opportunity to gain autonomy from foreign powers while challenging the communist-led Democratic Republic of Vietnam's claims to rule the country. At the Geneva conference, held in part to determine Vietnam's political future after the French defeat at Điện Biên Phủ in March 1954, American diplomatic pressure ensured that the State of Vietnam would control the territory south of the seventeenth parallel until re-unification elections scheduled for two years later. In July 1955, Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm, with American support, announced that the State of Vietnam would not participate in reunification elections. In October 1955, he organized a referendum that successfully ousted Bảo Đại, the head of state. Three days later, he proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam, with him as president. The Republic of Vietnam existed until April 30, 1975, when its president Dương Văn Minh surrendered to the forces of the communist People's Army of North Vietnam.

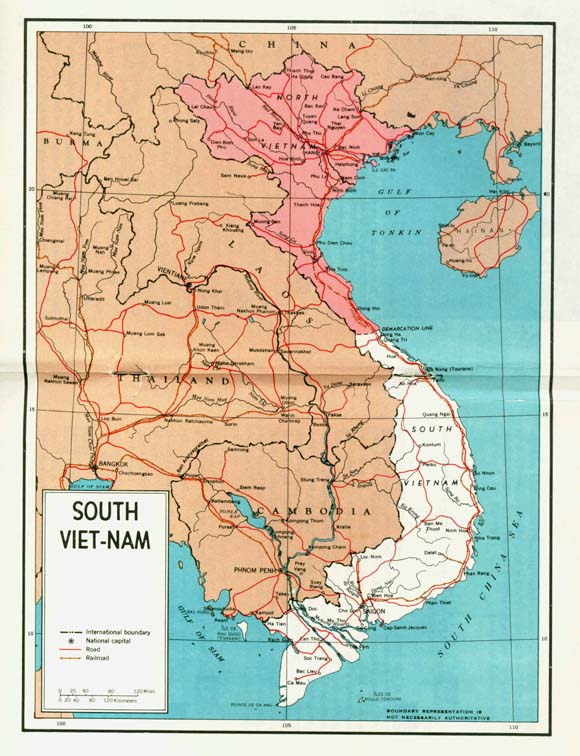

The social, economic and environmental landscape of South Vietnam was a major factor in the course of the Vietnam War. Southern Vietnam, most notably the Mekong Delta, is an ethnically and religiously diverse region that was only integrated into the Vietnamese kingdom in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the French colonial period, this extremely fertile region was the main source of rice and rubber exports from the colony. Colonial economic regimes created a highly unequal and stratified society in the Mekong Delta that Ngô Đình Diệm's tepid land reforms in the 1950s did little to address. In the Mekong Delta, economic inequality and a desire for socio-cultural autonomy was a principal factor behind the resurgence of opposition to the Republic of Vietnam in its early years of existence. As the war in South Vietnam intensified in the 1960s, the jungle of the Mekong Delta provided important protection for guerilla fighters, and resulted in widespread American-led campaigns of environmental destruction. South Vietnam is also home to a large range of ethnic minority groups, most of them in highland areas north of the Mekong Delta and west of the coast. Many of these groups sought autonomy from both the Republic of Vietnam as well as the communist-led insurgency. During the war, the American military armed and supported ethnic minority militias as weapons against communist forces. As a result, many of these groups suffered significant political, social and economic discrimination and repression after the communist victory in 1975.

In 1949, the political leadership of the newly created State of Vietnam drew primarily from the non-communist nationalist leaders forced out of political power by the 1945 revolution and the gradual communist takeover of the revolutionary Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Among these were leaders who desired a continued close relationship with France, and others calling for total autonomy for the new non-communist state. The head of state was the former emperor Bảo Đại, whose personal ambitions to return to power after his forced abdication in 1945 dovetailed with French desires for a well known and politically sympathetic figure at the head of the new state. Ngô Đình Diệm, like many non-communist Vietnamese nationalists, opposed French influence over the State of Vietnam and initially refused involvement with its leadership. At the end of the First Indochina War, as French influence in Vietnam faded, many Vietnamese nationalists rallied to the State of Vietnam, whether out of support or political opportunism. Among these was Ngô Đình Diệm, who spent much of the second half of the First Indochina War cultivating American support. Diệm, like the second-longest serving president of South Vietnam Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, was Catholic, and drew significant support from the minority Catholic population and Church organizations. After the coup against Ngô Đình Diệm in 1963, leaders of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam dominated the political leadership of the Republic of Vietnam until the return to civilian rule under Nguyễn Văn Thiệu in 1968.

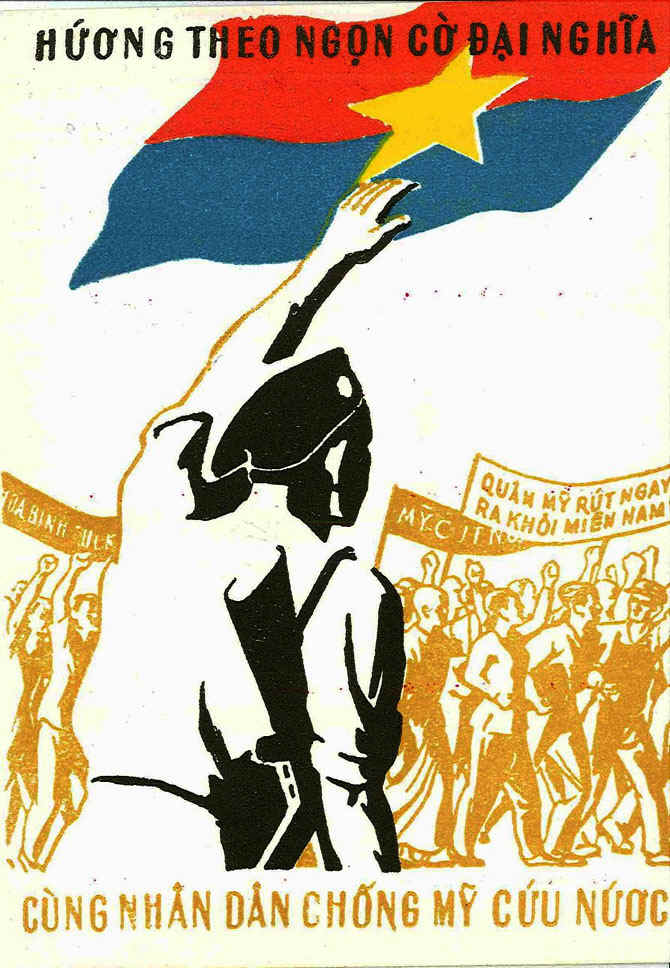

The leadership of the Republic of Vietnam faced broad and diverse opposition from the beginning. During the First Indochina War, a range of forces in southern Vietnam fought the French and one another for political autonomy. Forces loyal to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, most of them sympathetic to communism, began a guerilla war against returning French forces in 1945, as did the militias of several religious groups, notably the syncretic Cao Đài and the millenarian Buddhist Hỏa Hào sect in the western Mekong Delta, as well as the Bình Xuyên, an organized crime syndicate that controlled much of the city of Saigon's gambling, prostitution, and drug activity. During the early part of the First Indochina War, these groups opposed each other as much as they did the French, leading to an extraordinary degree of violence in the south. Although the religious sects and the Bình Xuyên reached an uneasy truce with the French after the creation of the State of Vietnam in 1949, they continued to push for political influence and autonomy from the new Vietnamese state and its army. In 1955, through a series of political deals and military campaigns, Ngô Đình Diệm successfully neutralized most of the opposition to his rule from the religious sects and the Bình Xuyên, and he kicked off a broad campaign to defeat the communist-led insurgency that decimated much of its organization. However, Diệm's unpopular and repressive policies, as well as a steady influx of manpower and resources from North Vietnam, revived and reorganized the communist-led movement under the banner of the National Liberation Front, an organization formed by North Vietnam in 1960 to lead southern military and political opposition to Diệm's rule. Finally, Diệm's rule, and the growing American influence in South Vietnamese politics, also alienated a range of urban political forces, notably left-leaning intellectuals and Buddhist leaders. These forces were an important factor in the political crisis in South Vietnam in 1963 that led to Ngô Đình Diệm's overthrow and death.